Entomophagy throughout the ages 🐞

Published:

Entomophagy, or the practice of eating insects, has been hailed as the panacea of our food system, with its innumerable health and environmental benefits.

Chimpanzees looking for termites

We often hear that humans have been eating insects for as long as they have been on earth, and so, the (mostly) Western aversion to insects is unjustified. But what evidence do we actually have of humans eating insects across history?

Our first clue to what our ancestors ate can be found by looking at our closest relatives. Today, chimps eat ants and termites by sticking a branch into termite mounds. Gorillas destroy these mounds with their fists and then scoop up the termites to eat them. A group of scientists experimented with bone tools mimicking those of Australopithecus, one of our ancient relatives (4 million years ago), and compared their wear and tear in different activities. What they found: Australopithecus most likely also used tools to dig up termites. While we don’t have much proof to whether Homo erectus (1.9 million years ago) ate insects, their much larger brain size suggests they needed lots of protein and makes it probable that they foraged for insects. Fossilised faeces from caves in North America contained insects (beetles, ants, larvae and lice) and arachnids (ticks and mites) while cave paintings in Spain (30–9,000 BC) showed insects being collected for food.

Texts and written accounts show that modern day humans have eaten insects in different forms around the world for thousands of years.

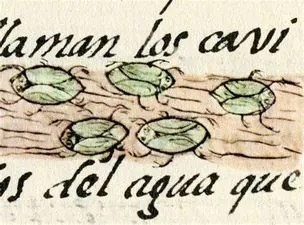

In the Americas, insect harvesting, notably cicadas, was common in American Indian societies before the European settlers arrived. Some communities even based their calendar on larvae life cycles. Insect species were also used for medicine and as hallucinogens. Insect fruitcakes were traded with white colonists in the Great Basin, and Missouri-based communities would sometimes eat locusts in times of locust swarms. In 1557, Sahugan recounted how Aztec royalty were given ahuauhtli (aquatic insect eggs nicknamed the Mexican caviar) during holy ceremonies. These eggs were also sold in local markets.

Sahugan-Historia de las cosas de la Nueva España

The first account of edible insects in Europe is found in Ancient Greece. Aristotle (384–322 BC) wrote in Historia Animalium about the cicada as a delicacy and as tasting best when full of eggs. Diodorus of Sicily (200 BC) called people from Ethiopia “eaters of locusts and grasshoppers”. In Ancient Rome, Pliny the Elder mentioned “cossus”, a dish consisting of larva, in his Historia Naturalis. More recently, there are sporadic accounts of German soldiers feeding on silkworms in Italy (17th century) and modern-day Ukrainians using an ant-based liquor as medicine in the 19th century.

In the Middle-East, Bodenheimer, author of a 1951 book on the history of insects, refers to accounts of locusts being served in the Neo-Assyrian empire (Nineveh, modern day Iraq) to kings at royal banquets around 8’000 BC. Religious texts also shed light on the food that was eaten in that region. Leviticus 11:21–22, from the Old Testament (~1’300 BC) says:

“There are, however, some flying insects that walk on all fours that you may eat: those that have jointed legs for hopping on the ground. Of these you may eat any kind of locust, katydid, cricket or grasshopper.”

Still today, this passage informs Jews on the types of insects that are kosher. While only a few Jewish communities have perpetuated this practice, it is experiencing a revival in the modern age.

In 1550, Leo Africanus of Morocco, wrote how communities in Arabia used locusts swarms as a food source:

“Nomads of Arabia and of Libya greet the appearance of locust swarms with joy. They boil and eat them, dry others in the sun and pound them into flour for future consumption.”

In addition, passages from the New Testament Mark 1–6 (~65 CE) and Matthew 3–4 (~80 CE) mention John the Baptist’s liking for locusts and wild honey. Nowadays, these passages are what drives the demand for products sold by Biblical Protein, aiming to recreate the diet of John the Baptist.

Biblical Protein recreating the diet of John the Baptist

Also, in Islamic scriptures are locusts often mentioned and approved for consumption.

“The Messenger of Allah was asked about locusts. He said: ‘(They are) the most numerous troop of Allah. I neither eat them nor forbid them.’” (Sunan Ibn Majah 3219)

“Two kinds of dead meat have been permitted to us: fish and locusts.” (Sunan Ibn Majah 3218)

“The wives of the Prophet used to give each other gifts of locusts on trays.” (Sunan Ibn Majah 3220)

“and we encountered a swarm of locusts or a type of locust. [..]The Prophet said: ‘Eat them for they are the game of the sea.’” (Sunan Ibn Majah 3222)

“We went on seven expeditions with Allah’s Messenger and ate locusts.” (Sahih Muslim 1952)

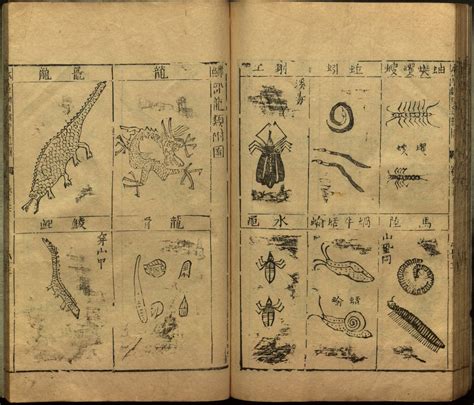

Moving east, evidence from China (2’500 BC) suggests the consumption of silkworm pupae for food and during the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644), traditional Chinese medicine (Li ShiZhen) used insects to cure various diseases.

Li Shizhen-Compendium of Materia Medica

Finally, until today, traditionally-living Australian Aborigines eat ants, moths, termites and grubs and use cockroaches (anaesthetic), tree ants (headaches and colds), termites (antidiarrheal agent) and grubs (wounds and burns) for medicinal purposes.

All this evidence begs the question: why have certain societies stopped eating insects while others such as the Australian Aborigines haven’t? The short answer is agriculture and domestication: it just wasn’t worth it anymore for some societies to hunt and rear insects in the wild. In addition, with the advent of farming, they increasingly became seen as a pest for crops and a poor man’s food. Other societies closer to the tropics (that’s where you find larger species) have kept on eating insects on a relatively small scale until today. However, a deep dive on the transition from insect rearing to mammalian domestication will be a topic for a future post, so keep your eyes open.

Now, startups such as Hargol and YumBug are looking to bring grasshoppers and crickets to the masses.

Yumbug are bringing crickets to the UK

While growing up in Israel in the 1950s, Dror Tamir saw his Yemenite and Moroccan Jewish neighbours eating grasshoppers during locusts swarm, as referenced by Leo Africanus of Morocco. This is what gave him the idea to found Hargol (Hebrew for grasshoppers), a commercial grasshopper farm, in 2014.

Hargol FoodTech-Commercial Grasshopper Farm

In this blog, I will be exploring the world of entomophagy: it’s history, the opportunities it opens and its ethical and practical challenges. Follow me or get in touch if you’d like to hear more and even learn how to start your own insect farm at home!