The carbon costs of Japan’s illegal scientific whaling 🐋

Published:

The Impact of Japan’s Scientific Research Whaling Programs on the Marine Ecosystem and the Carbon Cycle.

The origins of whaling

The “Tragedy of the Commons”, a term coined by Hardin, explains how natural resources will inevitably be overexploited because they are common goods: non-excludable (anybody can access it) but rivalrous (there is a finite supply of it).

Whaling is a sombre example of this. Whales have been hunted since prehistoric times, but until the 19th century, on a relatively small scale. Enter the explosive harpoon and the steam engine, and whaling took off. Whale blubber was used in oil lamps, soap, and margarine. Whale bones were used for manufacturing daily products such as corsets and umbrellas. Whale meat, while not considered particularly luxurious, was and still is a staple food in Northern and Arctic communities. Whale meat was also un-rationed during the 2nd World War in Japan and the United Kingdom, as protein supplies dipped.

Fisherman hunting for whales

In 1927, the League of Nations recognised the growing issue of whaling leading to species extinction, but whaling companies were powerful, and any suggested measures struggled to be enforced through global governance. The International Whaling Commission (IWC) was established in 1946 with the aim

“to provide for the proper conservation of whale stocks and thus make possible the orderly development of the whaling industry”

Despite the IWC’s focusing on the interests of the whaling industry, it was still forced to impose a whaling moratorium (zero-catch limit) from 1986, to replenish whale stocks and avoid the extinction of certain whale species. Japan famously opposed this measure but backed down due to the US threatening Japanese fishing quotas in US waters.

However, Japan found a way to continue whaling, through scientific permits, from 1985 to 2019, to research whales’ behaviour and inform sustainable whaling. After having published a suspiciously small number of scientific papers, whaling in an Australian Whale Sanctuary and investigators finding whale meat in Japanese seafood markets, these whaling practices were deemed illegal by the International Court of Justice in 2014. The IWC then confirmed in 2018 that its purpose was to conserve and protect whales for perpetuity, as opposed to supporting sustainable whaling, as Japan argued. This prompted Japan to leave the IWC and re-establish commercial whaling in its own exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

Since the 1986 moratorium, 40’000 whales have been killed. Japan has killed nearly 20’000 Minke Whales during that period, with 31% of those catches not being under scientific permits (commercial catches, by-catch or under objection by the IWC).

Japan re-established commercial whaling in 2019

Whales form a crucial part of the Carbon Cycle

Earth’s diverse ecosystems regulate the concentration of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Whales themselves store, sequester, and export carbon from the atmosphere. Whales also enhance the productivity of phytoplankton, who perform photosynthesis. Photosynthesis is a process which transforms carbon dioxide into oxygen. In marine environments, phytoplankton, which have chlorophyll, convert water, and carbon dioxide into carbohydrates and oxygen, using up light and nutrients.

Whale Pump: Whales breath at the surface and dive down to feed. Thanks to this vertical movement in the sea, it brings up and mixes the nutrients and phytoplankton from the bottom of the sea to the surface, where photosynthesis can be achieved thanks to the presence of sun-rays.

Whale Defecation: As they defecate close to the surface, whales provide phytoplankton many crucial nutrients, especially iron and ammonium, increasing their photosynthesis productivity.

Bio-mixing: Whales travel substantial distances bringing nutrients from feeding waters (high latitude), where nutrients are ingested, to breeding waters (low latitude), where nutrients are released. This ensures photosynthesis can be achieved on a much larger scale, across the whole ocean.

Biomass Carbon: Whales, as large mammals, store huge amounts of carbon inside of their body throughout their lifespan. Larger sized animals have a higher metabolic efficiency, meaning they store larger amount of carbon compared to smaller animals relative to their size. This is because they need less food per unit of mass, thus expend less energy, use less oxygen and do not release as much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. For example, a Blue Whale diet would feed 1,500 penguins, but the latter’s collective biomass would be 50% lower than that of a Blue Whale.

Dead-fall Carbon: When whales die, their carcass sinks down into the deep sea, trapping large amounts of carbon dioxide in their bodies. This carbon stays at the bottom of the ocean and slowly incorporates itself in the ocean’s floor sediments, enriching it in the process.

Carbon export of Japan’s scientific program

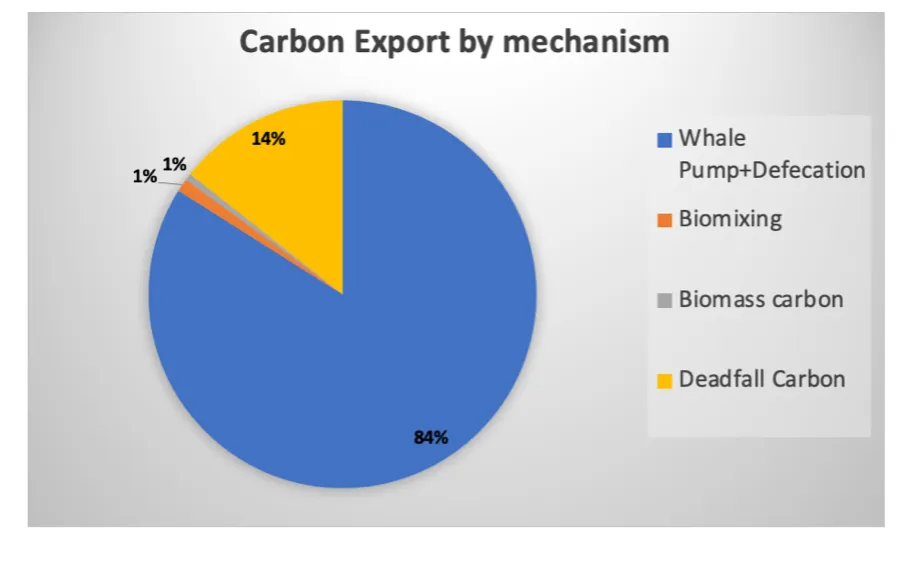

By separating each of these mechanisms, we can estimate how much carbon a whale exports from the atmosphere during its lifetime. Let’s look at Minke Whales, they were the species that were predominantly killed by Japan under their 6 scientific programs, between 1985 and 2019 (Annex A).

Over a year, a single Minke Whale exports 3.17 tons of carbon (Annex B) from the atmosphere, which a majority comes from the increased productivity of the phytoplankton and photosynthesis thanks to the whale’s movements and defecations. This is less than the amount of CO2 a typical car in the US produces, 4.6 tons.

Now let’s look at how much this represents over the course of a whale’s life. We must first make some assumptions:

- We consider all the whales that were killed and their (supposed) calves (first generation).

- The whales that were killed had 25 years left to live. The average lifespan of a Minke Whale is 50 years.

- The adult survival rate is 95%.

- Half of the whaled population were females, and each gave birth to a calf. Female Minke Whales have a gestation period of 10 months, then spend 4 to 6 months nursing their calf, so they usually give birth every 1.5–2 years.

- We only consider the first generation of calves as modelling the population dynamics of the subsequent generations requires too much forecasting, with many uncertain variables such as future whaling quotas, the population dynamics of whales and of their preys and predators, as well as the consequences of climate change.

- The calf survival rate is 80%, and a typical Minke Whale will live for 50 years.

- A calf grows in size at a constant rate of 53.4% per year, to reach its full size at age 8.

- A calf weighs around 1,000 lbs when born, and will reach around 20,000 lbs as an adult, reaching sexual maturity at 8 years old.

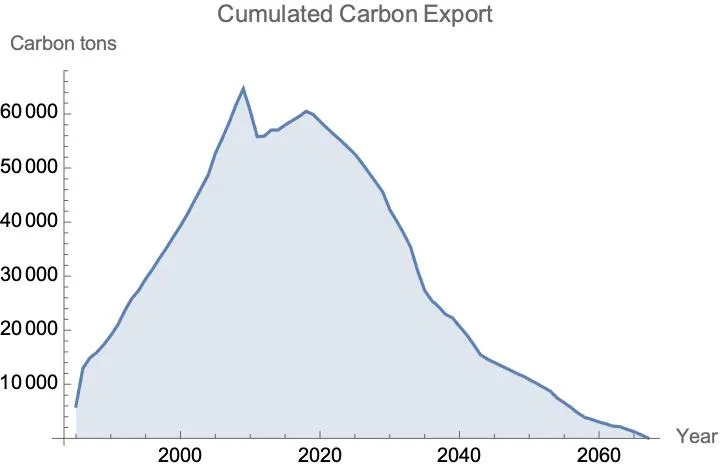

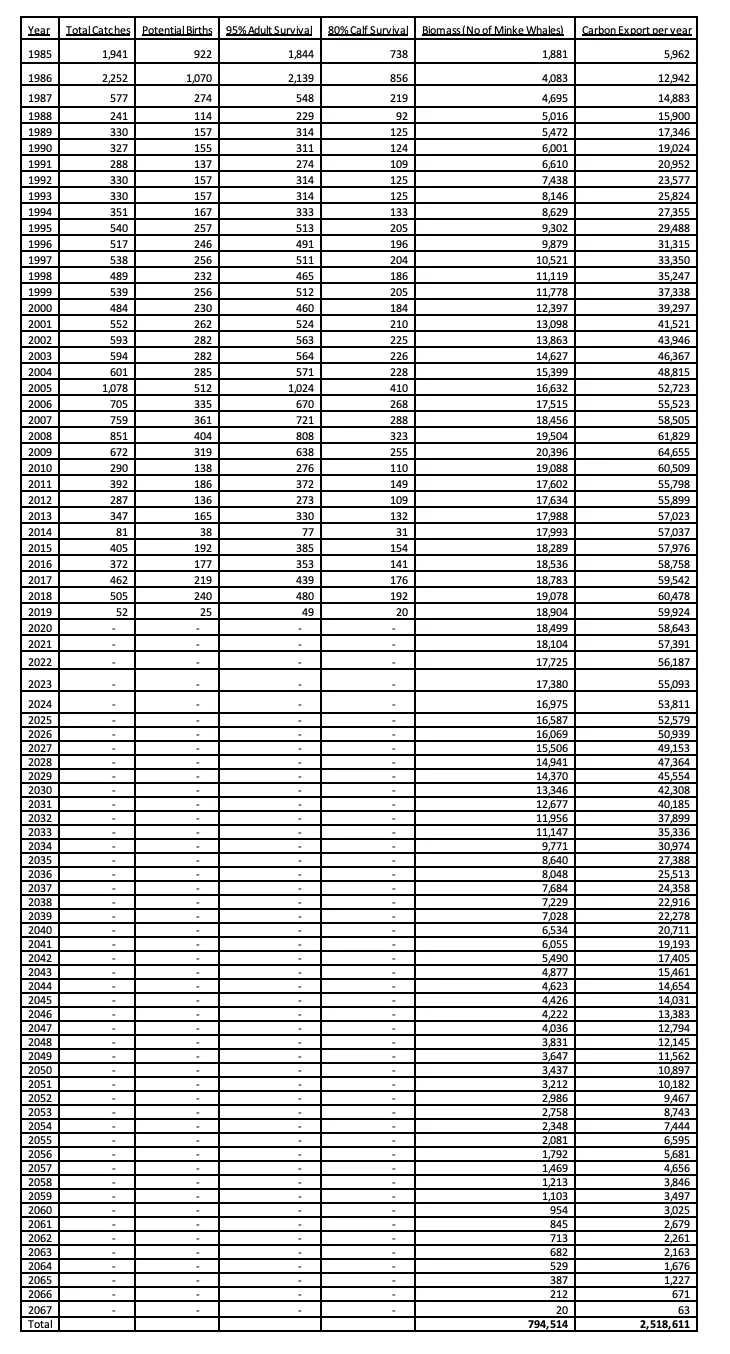

Between 1985, when the first whale was killed, and 2067, when the last first-generation calf would have died (Annex C), the total amount of carbon that could have been exported was 2.01 million tons of carbon dioxide. The peak was in 2009, when there were 20,396 whales that were potentially missing from the Minke Whale population due to Japanese whaling.

This number of 2.52 million tons of CO2 is equivalent to the carbon export of 1.4 million trees during the same period, nearly equivalent to the number of trees in Tokyo.

This figure is pale in comparison to what other industries emit in Japan. For example, The total amount of carbon potentially exported by these whales over 83 years represents only 13% of the CO2 emitted by the transportation industry in Japan, in 2019 only!

Dead whale being brought back to port

Pricing carbon

To combat climate change and reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, governments have attempted to put a price on carbon emissions. This price enables governments to make pay producers for the emissions they emit. This is a typical tool for economists, where the cost of negative externalities (GHG emissions) is no longer borne by the whole community but by those who are responsible for it (we are “internalising” externalities).

Japan currently has a carbon tax at 2.65USD per ton of CO2, which means that its illegal scientific whaling program cost 6.45million USD in terms of carbon emissions.

However, this tax is one of the lowest amongst developed countries. When we look at Emissions Trading Schemes (ETS), where emitters can trade emission units to meet their emission targets, it is a different story. The EU ETS, one of the most established emissions trading systems, currently (21 January 2022) trades a ton of CO2 at 84.11 USD. This would bring the cost of Japan’s whaling program at 211.96 million USD (Annex D)

In addition to these carbon costs, Japan spent 44,000 USD annually on their scientific whale research only, amounting to 1.54 million USD over this 35-year period.

Japan has also spent a substantial amount of money on “convincing” other members of the IWC to vote in their favour through trade deals and foreign aid.

Finally, whales can have an intrinsic commercial value. An Australian study estimated that a Humpback Whale has a present value of up to 903,899 USD from whale watching only.

Food for thought

The carbon exporting capacity of whales is truly incredible, and they play an integral part in the marine ecosystem. But we cannot disregard the fact that they are completely overshadowed by the magnitude of human emissions. When a single Minke Whale exports less than what a car emits during a year, and there are 424 times more cars than whales on earth today, it shows how big of a problem we have. We’ve managed to bring our natural ecosystem dangerously out of balance and saving whales will not be enough.

Japan keeps on whaling today

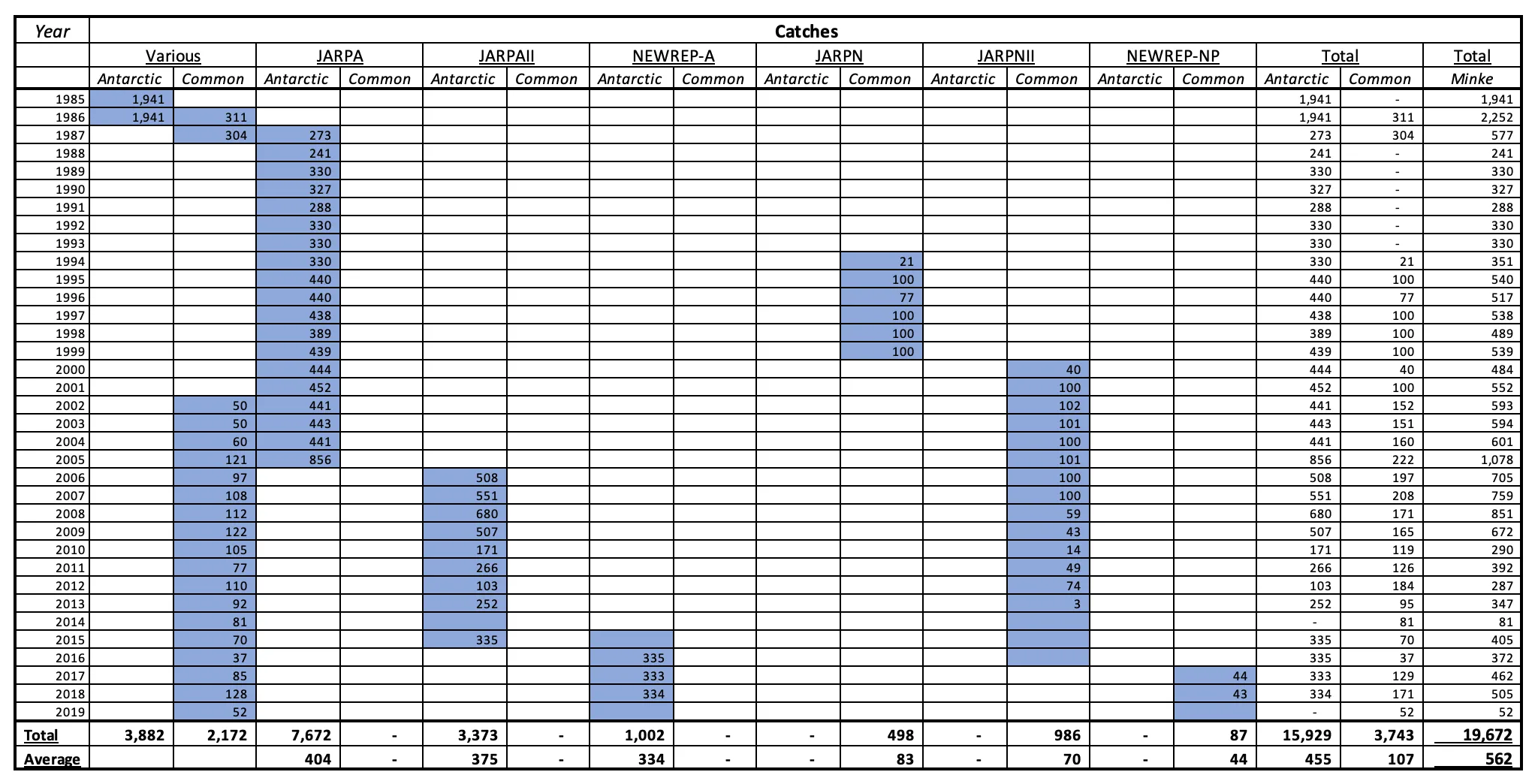

Annex A

Number of catches per year, by scientific program and Minke Whale species

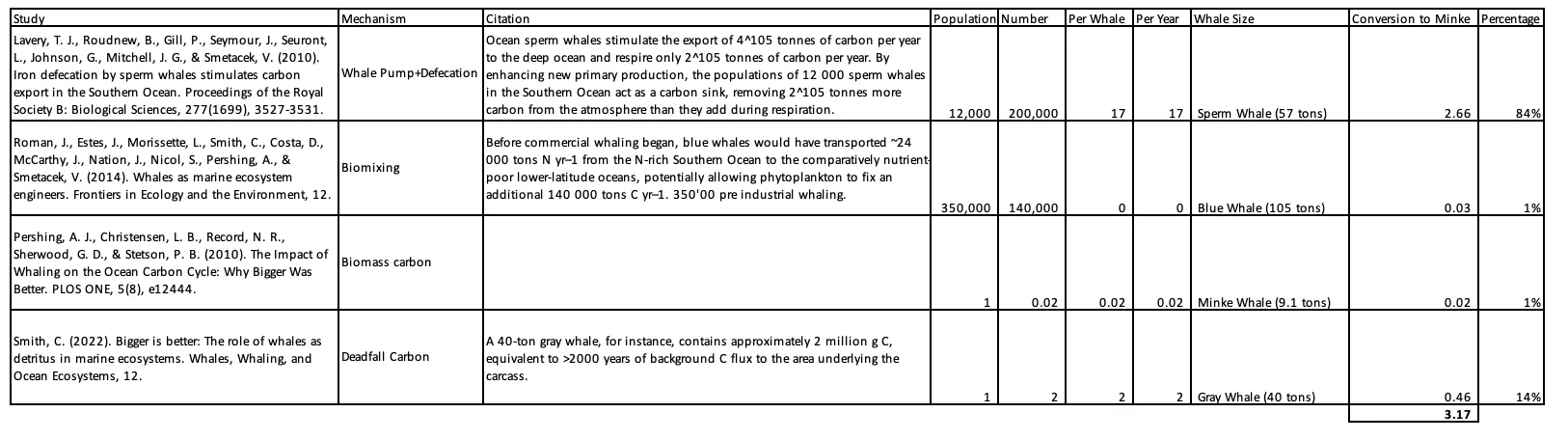

Annex B

Carbon export of a Minke Whale, broken down by type of process

Why this might be an overestimate:

- Minke Whales are smaller than the whales studied in these papers, meaning they are less efficient when exporting carbon because smaller animals have a lower metabolic efficiency and use up oxygen quicker than larger animals, thus breathing more C02 relative to their bodyweight.

- When a species starts shrinking, other species population increases, which might offset the initial decrease in the carbon export due to their death.

Why this might be an underestimate:

- Predators, for example Killer Whales for Minke, do not have access to as much food as before, due to whaling, their population might decrease, they might not gain as much weight, which might further the carbon export potential of other marine mammals.

- We have not considered the carbon emitted from polluting vessels, factories and equipment needed to kill these whales and analyse them for research purposes.

Annex C

Population dynamics of whales killed and their calves (first-generation)

Annex D

Regarding carbon pricing, ETS has only been in place for the last 15 years, and thus is hard to apply today’s carbon prices to a time where carbon was not priced. Similarly, we could expect carbon prices to increase in the future, as governments reduce emission quotas to meet their emission targets. We have not taken this into account as modelling the future price of ETS is too inaccurate.