When relationships aren’t as exclusive as you think 🔗

Published:

Instrumental Variables chat

Causal Inference is fascinating to me because it makes a bold attempt to identify causality in the impossibly complex system that is our society and economy. As with cell biologists or neuroscientists, economists and social scientists are dealing with a system we will never fully understand. However, I am inspired by the attempt to identify causal relationships in a noisy world.

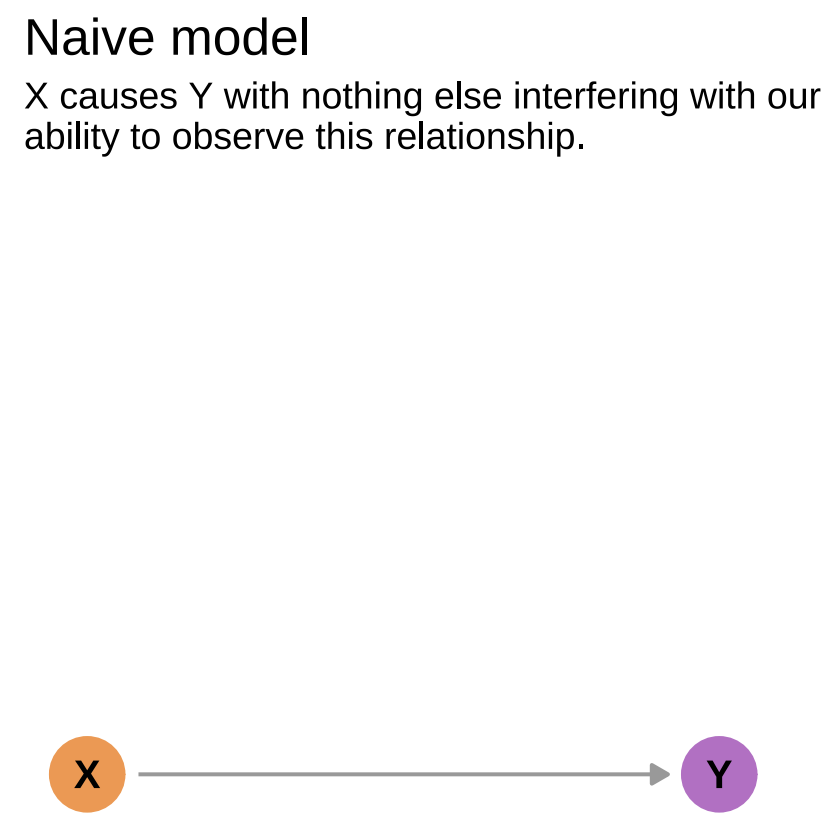

The relationship a typical study would attempt to measure would be the following:

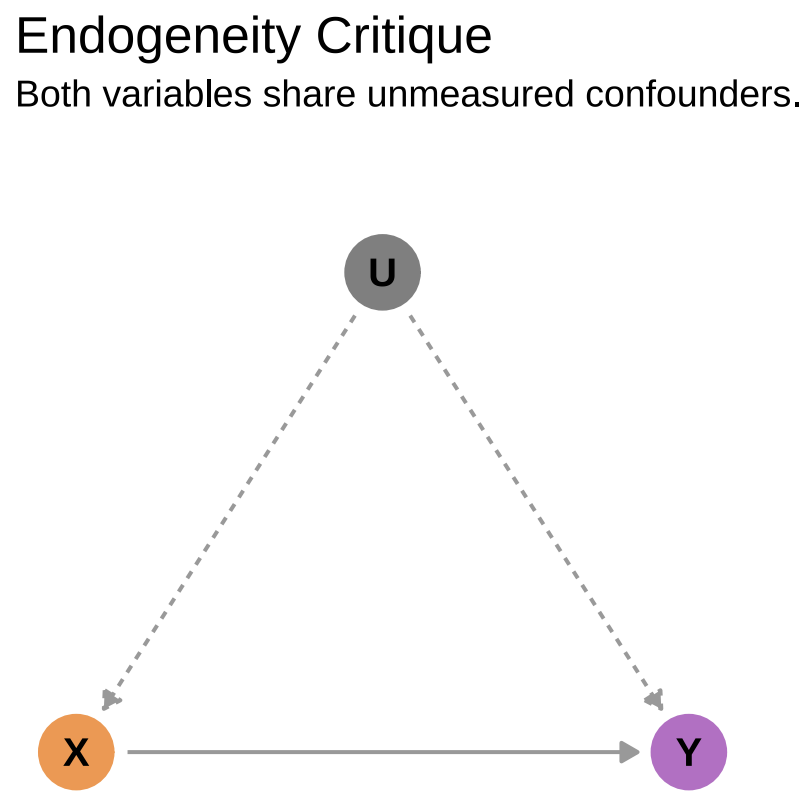

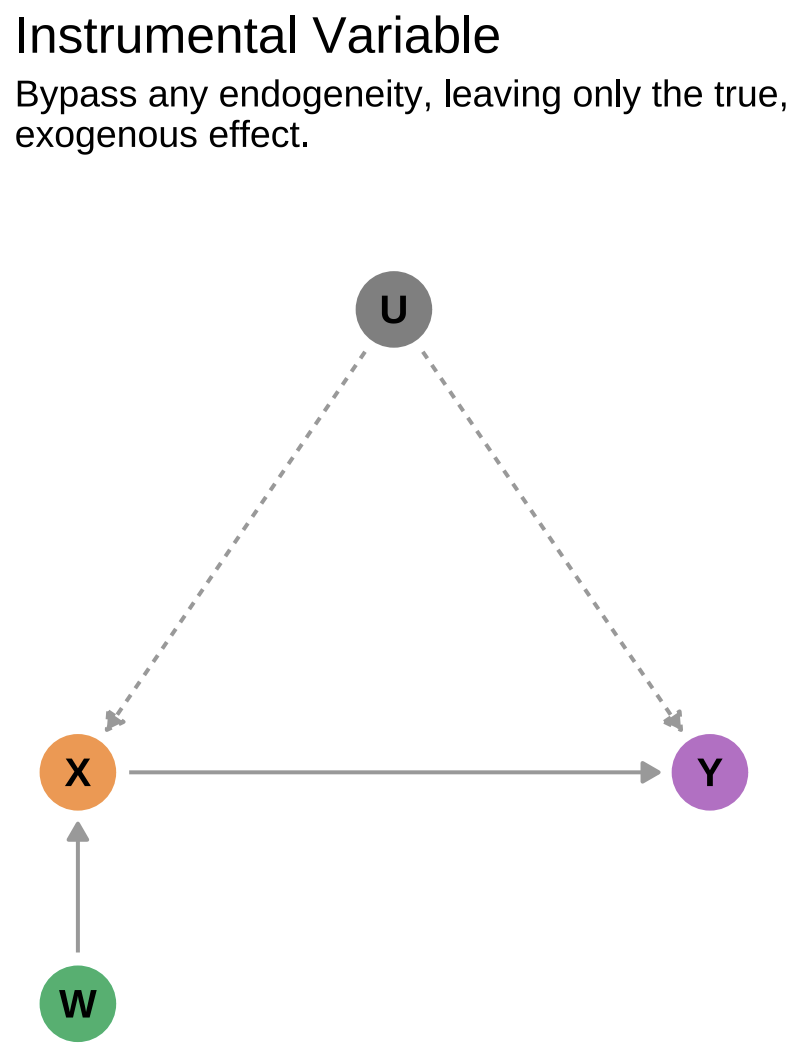

One of the four assumptions that needs to be made for this relationship to be valid and used in a simple linear regression is that a third factor, U, should not impact the independent variable (X): they should not be correlated. This is the zero conditional mean assumption. However, in real life, this is often violated, there often is a third factor that impacts both the independent (X) and dependent (Y) variables:

The dotted lines of U imply that these relationships are unmeasurable. The issue here is that we cannot isolate the effects of X on Y because U is impacting both of them. We also call this Omitted Variables Bias because the variables we do not measure have an impact on our (presumed) causal effect.

What if we could find another variable, W, that impacted X but was not impacted by U and did not affect Y. This is the intuition behind the Instrumental Variable (IV) technique, where W is the instrument. The aim is to avoid the bias introduced by U by going from W to X to Y.

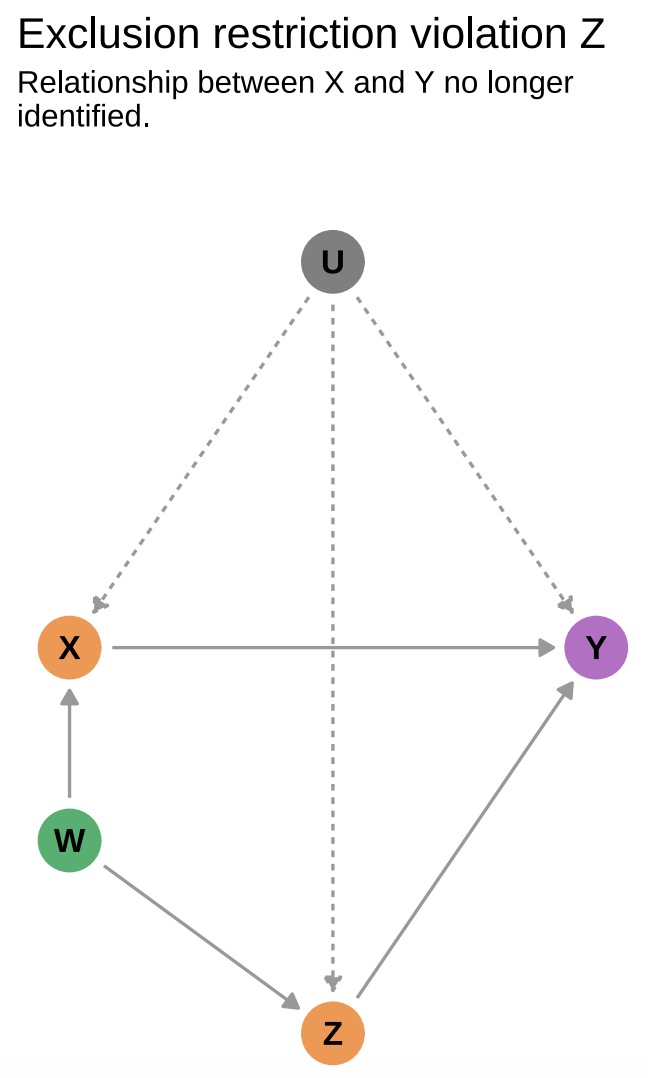

There is one key assumption here: the exclusion restriction. W should not impact Y in any way. The situation we are trying to avoid is the following:

This exclusion restriction is untestable, making the choice of IVs sometimes debatable (at best) or implausible and outright wrong (at worst).

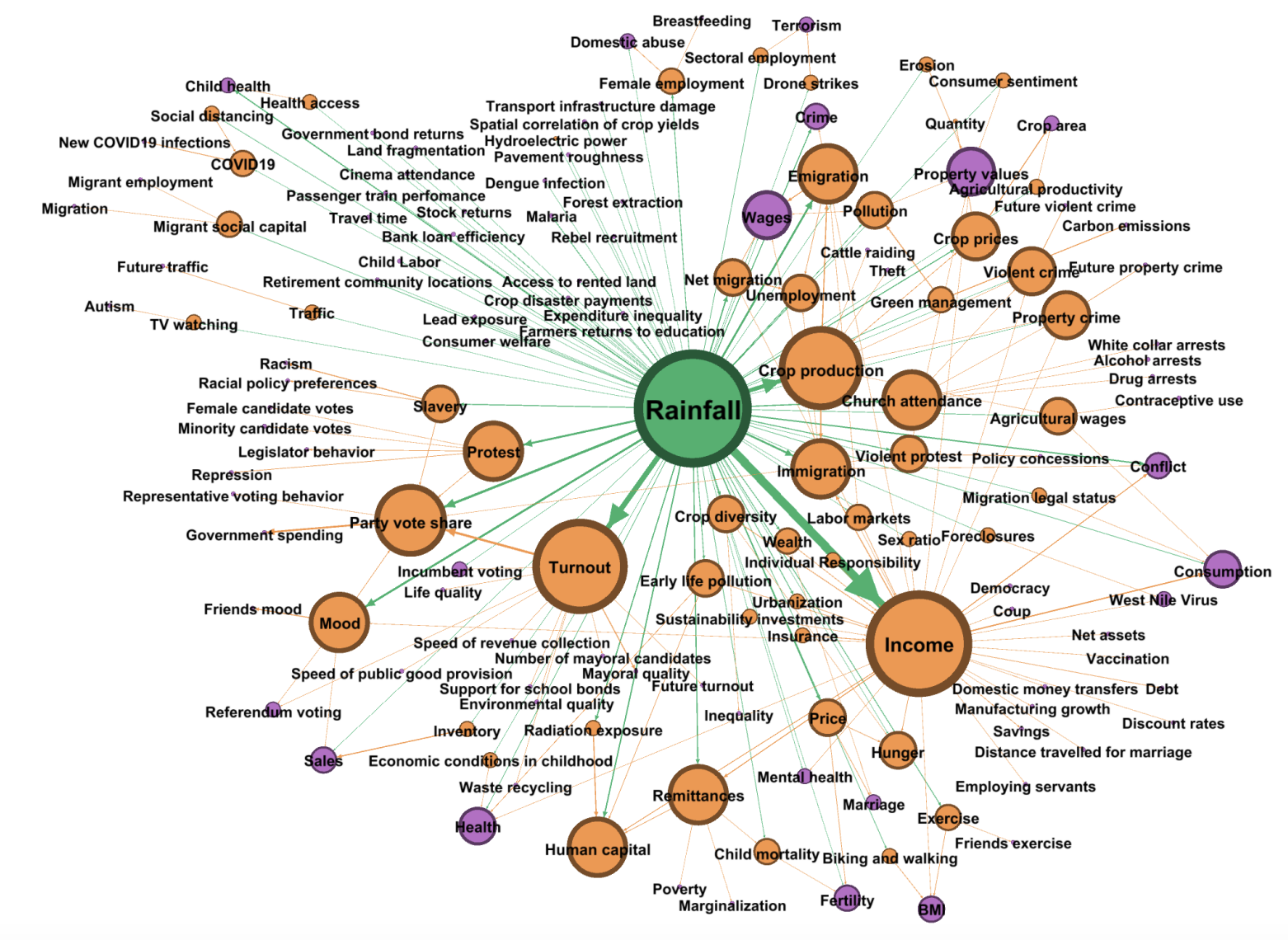

An interesting example of IV in practice is by Miguel, Satyanath, and Sergenti (2004) They were trying to find the relationship between economic downturns and civil conflicts in sub-Saharan Africa. As one would expect, other variables could impact both economic growth and the occurrence of conflict: corruption, healthcare policies, education. As a result, they used rainfall as an IV. Since the countries they were looking at were largely agrarian communities, they made the assumption that rainfall would have a strong effect on people’s income and the economic growth of a region, without directly causing conflict in itself. One could even argue that more rainfall prevents people from leaving their home and engaging in conflict.

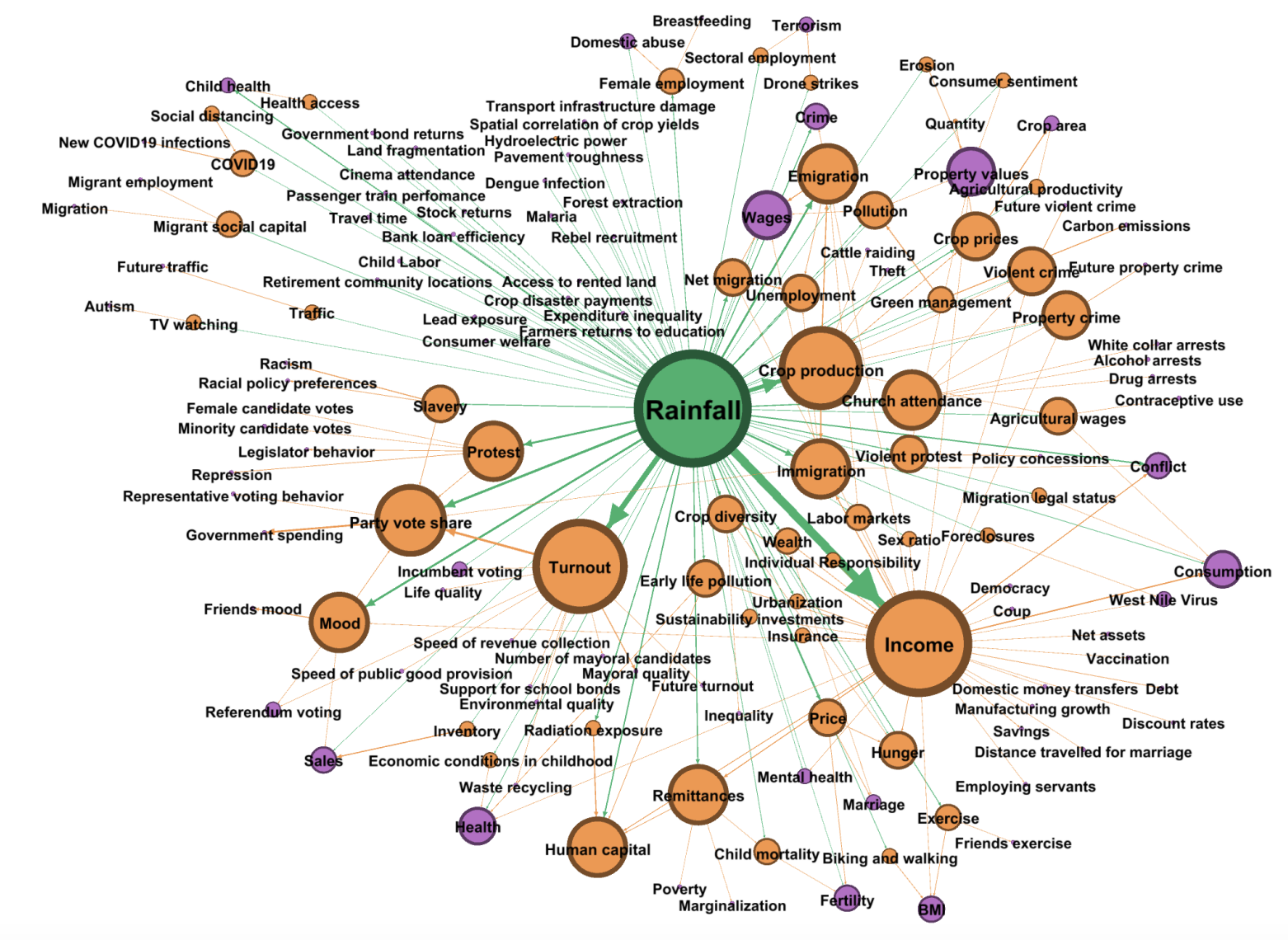

This use of rainfall and weather is very common as an IV in economic literature. However, some have put into the question the validity of weather as an IV, especially as it may often violate the all-important exclusion restriction.

A fascinating paper published by Mellon (2022) investigates this issue. He looked at nearly 300 studies where weather was used as an IV and found that two thirds potentially violated the exclusion restriction. The following graph summarises the idea of the paper:

This seems like a much more plausible way of representing our world, doesn’t it?

These exclusion restrictions violations that Mellon finds could suggest that some of the results from these studies are biased, or even invalid. He does not say that this is the case: his point is that (too) many IV studies are poorly designed.

Although IV choice might seem to be somewhat of a stab in the dark, as we cannot formerly test it, Mellon does suggest some ways in which you can be more confident that your IV is not violating the exclusion restriction.

Use domain knowledge. Nobody has a better intuition than an expert that has studied a field for a long time and has a good idea of what the mechanisms are. This is never perfect but should definitely be leveraged, humbly.

Employ statistical tests such as the Sargan-Hansen test and the zero first-stage test. The latter is the most common: it tests whether the instrument (W) is correlated with the outcome (Y).

Mellon ends with a great idea from Cunningham (2018). The latter argues that a good test for an IV is asking yourself if the link between W and Y is ‘ridiculous’ or not? It should be obvious to most people that W and Y are independent of each other.

This is why I find causal inference so fascinating: it combines rigorous statistical techniques with qualitative analysis and human intuition: something machines are still not able to do!

References:

Cunningham, Scott. 2018. Causal Inference: The Mixtape. https://mixtape.scunning.com/

Mellon, Jonathan, Rain, Rain, Go Away: 192 Potential Exclusion-Restriction Violations for Studies Using Weather as an Instrumental Variable (July 18, 2022). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3715610 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3715610

Miguel, E., Satyanath, S., & Sergenti, E. (2004). Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: An Instrumental Variables Approach. Journal of Political Economy, 112(4), 725–753. https://doi.org/10.1086/421174