Graphing Complexity: Designing an Awesome Graph Database in Neo4j - Part 1 🌐

Published:

“Mankind invented a system to cope with the fact that we are so intrinsically lousy at manipulating numbers. It’s called the Graph.” - Charlie Munger

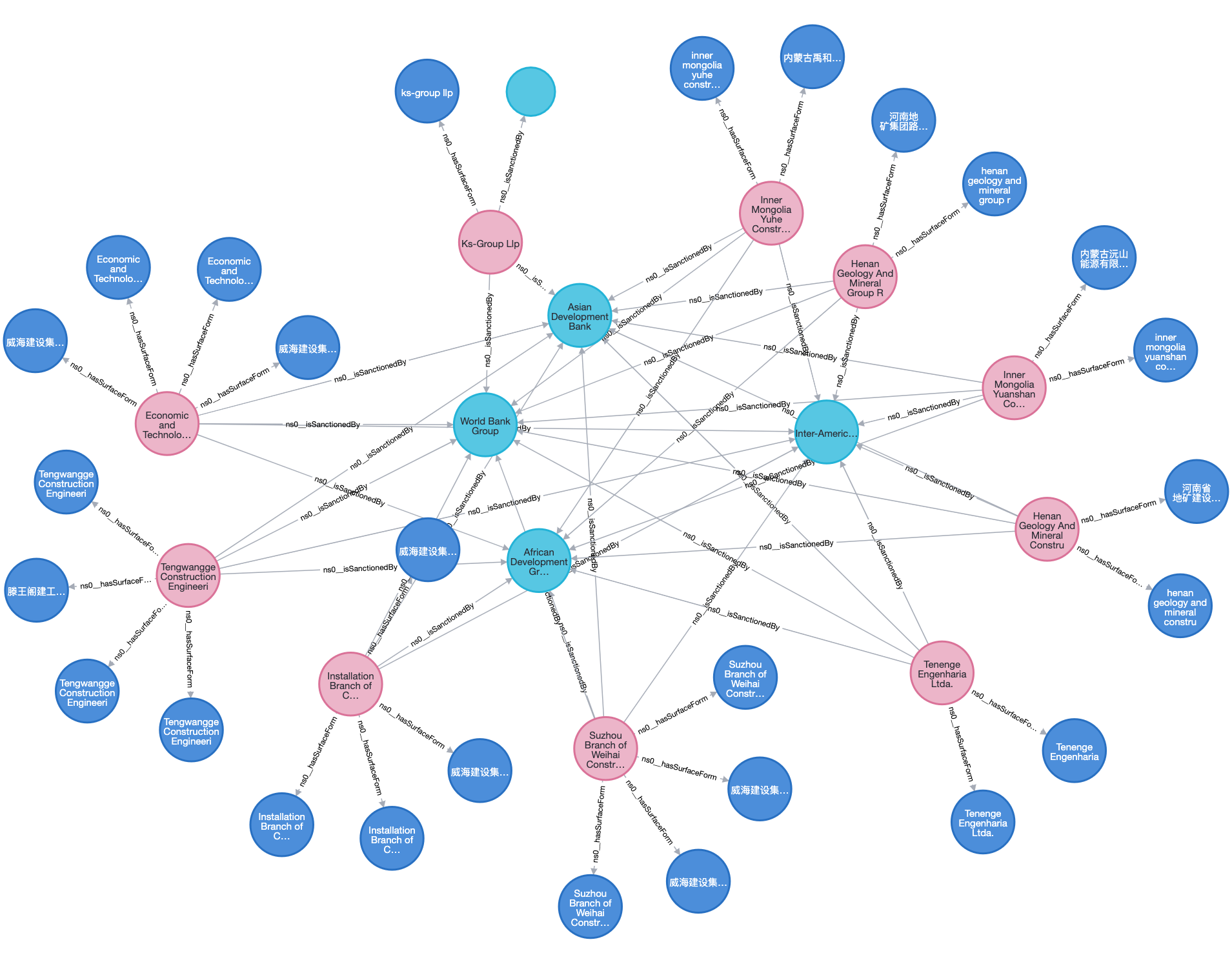

Data from OpenSanctions.

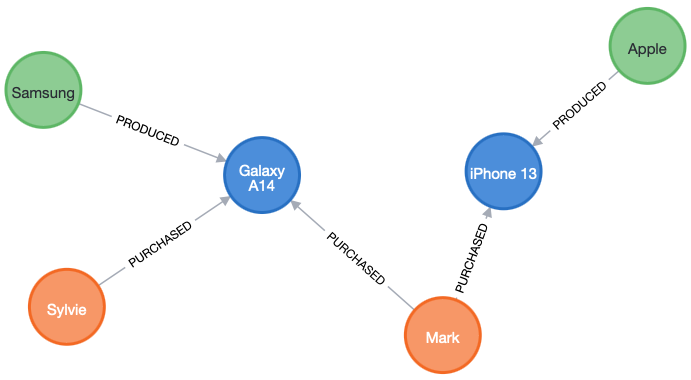

A Graph (Graph DB) uses nodes and relationships to model information and their interrelations. This is unlike a table, like in Excel, or a dictionary format, like a JSON. A Graph DB is an incredibly powerful tool to represent real-life data. Social relations, food webs, and the banking system are some of countless examples of how graphs and networks live all around us.

A Graph DB has many benefits. All SQL users will be happy to hear that no JOINs are needed across multiple tables. Every data user’s worst nightmare is avoided in Graph DBs, which makes data retrieval much easier, smoother, and more performant. This focus on data retrieval is in contrast with the emphasis on data storage of common relational databases. The door then opens up for much more complex querying, uncovering hidden information, and non-obvious and indirect relationships.

Moreover, Graph DBs do not have an intrinsic schema: users can create data models from scratch but also easily modify and expand them whenever needed, making them very flexible as business needs and data changes. In the same vein, extending and scaling a Graph DB is straightforward; you just add more information.

Here, we will discuss how to design a Graph DB hosted on Neo4j. However, most of these design decisions and practices are universal and not software-specific. In addition, the query language used in Neo4j is CYPHER, a powerful graph query language inspired by SQL. Tips on how to improve query performance might be more specific to CYPHER and might not always apply to other graph query languages.

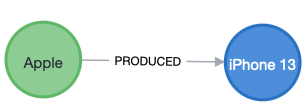

First, Graph DBs usually use the Resource Description Framework (RDF):

Subject – Predicate -> Object

The goal of a Graph DB is heavily dependent on the use case and business question at hand. If we can generalize, a Graph DB should enable us to:

1. Organize data in an intuitive and logical structure.

Intuitive and ease-of-use enables users and developers to spend as little time as possible on understanding the data model.

2. Flexibly scale and make changes to the data.

Business requirements, business questions, and data change all the time. Let’s avoid creating a brand-new Graph DB every time that happens.

3. Query data efficiently.

Now comes the concept of traversal. A Graph Traversal is the process of visiting nodes and relationships when looking for data. The smaller the traversal, the more efficient and fast a query will be. A Graph DB should aim to decrease the traversal size of queries by reducing the number of nodes and relations it will have to evaluate.

Graph queries start at a well-defined starting point and then crawl out from there. The queries will only evaluate the parts of the Graph that are connected to the starting points. Ideally, queries are written to make the starting point as specific as possible. This is only possible if the Graph DB is designed in a way that allows queries to do that, thanks to the right combination of labels, nodes, relationships, and properties.

Usually, traversing a graph by filtering for node labels and relationship types will be faster than evaluating the properties of nodes/relationships, as the starting point will be more limited, and labels/types are more easily evaluated, as we will see below.

Why should you keep on reading this?

Correctly modeling a Graph DB from the start is incredibly important because it will enable us to make non-breaking changes and extend the DB in a seamless and backward-compatible fashion. We will look at the four building blocks of a Graph DB and what to take into consideration when making design decisions.

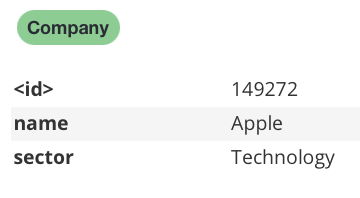

1. Nodes

Nodes represent entities, something that is tangible: a person, a company, a country, but also a gender, an address. They are complex value types and can contain properties, for example, the name of a company or a label, Company.

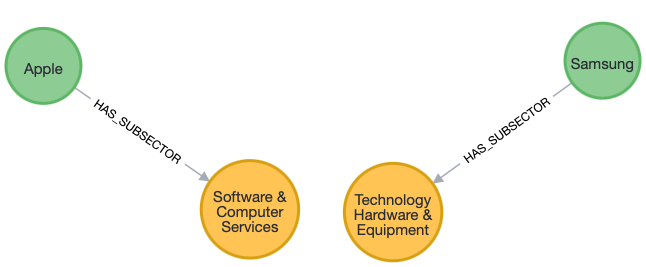

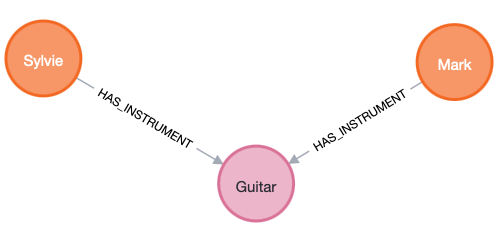

Separate a property into a separate node when:

- You need to look up other nodes that share the same property value so that you can filter by relation as opposed to property value.

- You want to capture other metadata about that category, meaning it is no longer a category but a complex object with properties.

- The cardinality of a categorical variable is very high, meaning there are many different categories.

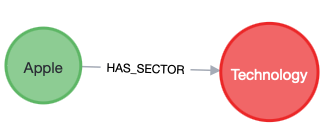

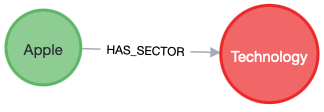

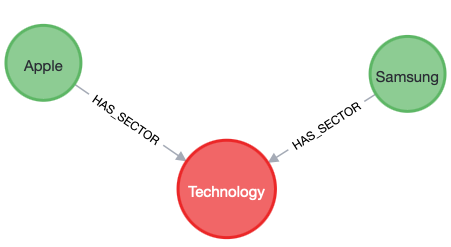

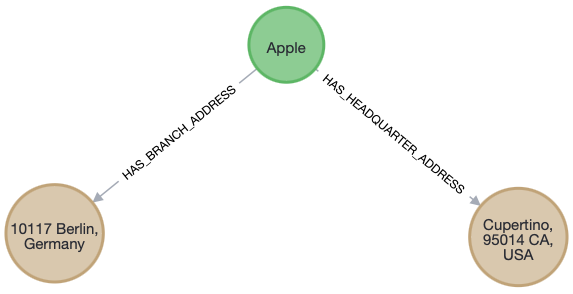

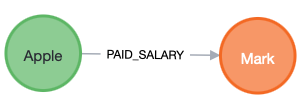

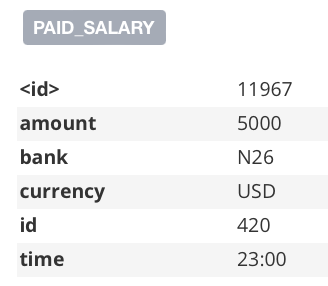

Here we can see how to separate a node property into a separate relationship.

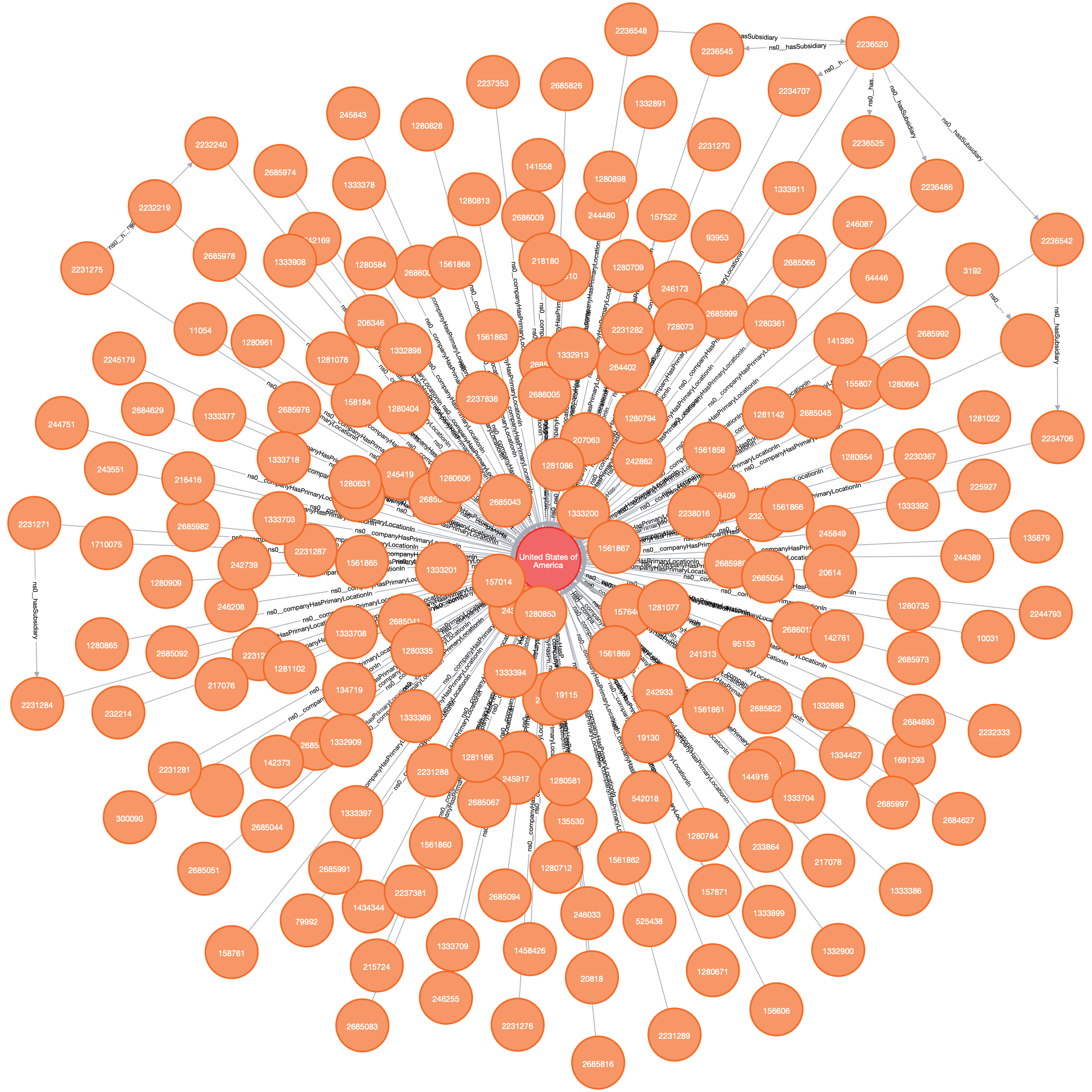

Supernodes

Supernodes are nodes that are connected to a vast number of other nodes. For example, the Male node will be related to half of all Person nodes in a graph. This can hugely increase the traversal size, impacting query performance.

Indeed, traversal speeds are typically constant with growing dataset sizes because everything is not connected to everything. This goes out of the window with supernodes. It puts the “hair into the hairball”. The unintended result is that more nodes and relations will be evaluated by a query, slowing down read operations.

Supernodes can come from the domain itself; we might just be dealing with a densely connected network, from our own modeling choices; as seen above, or when data might have outgrown the model.

A solution to supernodes is to make relations and nodes more specific. For example, adding a direction to a relationship, or adding a label to the Male node, which conveys the sexual orientation of the person. We could have Male:Heterosexual and Male:Homosexual to split out the Male node into two.

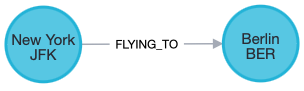

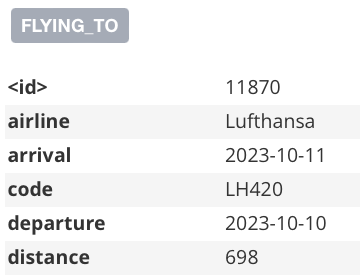

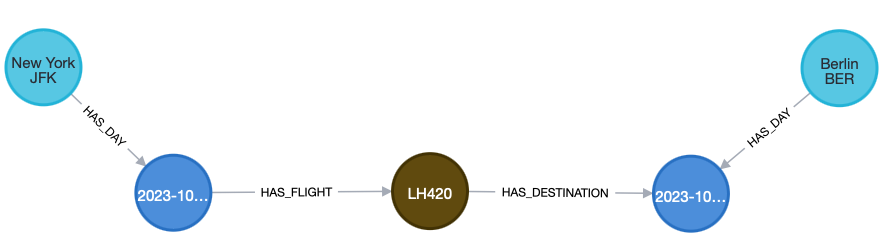

Below is an example of how we can split up a flight, which was initially a relationship into separate nodes. Here we avoid the JFK and BER Airport nodes to have an obscene amount of relations going out from them, one for every flight. Instead, we have one for every day.

Into:

Note that some supernodes might not always be that big of a problem if that node is not used in complex queries.

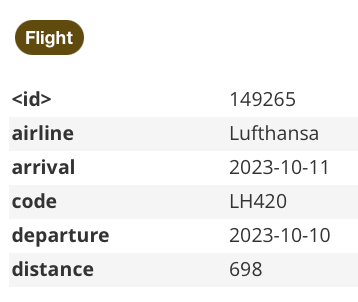

2. Relationships

Relationships enable information to be transformed into knowledge. How things are interrelated is the real power of a Graph DB.

Relationships have types and can contain properties, usually the quality or weight of a relationship, or other metadata linked to time and space.

Relationships also have a direction, and nodes can point to themselves. However, no relationship can be “dangling”: missing a start or end node. Finally, we don’t need to use null values to represent the absence of a connection.

Relationships are verbs:

HAS A: this expresses a part/whole relationship, AKA “composition.”

(:Company)-[HAS_SECTOR]->(:Sector).

IS A: this expresses an inheritance relationship between a parent and a child.

(:Person)-[IS_A]->(:Employee)

Functional: the relationship acts like a proper function, meaning that given a single domain, there can be only one range node.

(:Person)-[HAS_HOME_ADDRESS ]->(:Address)

Transitive: if the relationship is true from A to B and from B to C, then it’s also true from A to C.

(grandfather:Person)-[:IS_RELATED_TO ]->(father:Person)-[:IS_RELATED_TO ]->(me:Person)-[:IS_RELATED_TO ]->(grandfather :Person)

Reflexive: it means that the relationship implies every node has one of these to itself.

(a:Person)-[:KNOWS]->(a:Person)

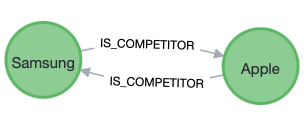

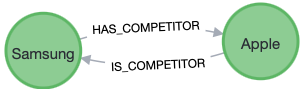

Symmetric: if the relationship is true one way, it’s true the other way too.

(a:Person)-[:KNOWS]->(b:Person)

Relationships are defined with regard to node instances, not classes of nodes. Two different pairs of nodes can be connected by the same relationship, allowing for structural variation in the domain. In addition, pairs of nodes can have multiple, different relationships.

As before, avoid loading too many properties into a relationship; it’s better to create multiple, more specific ones.

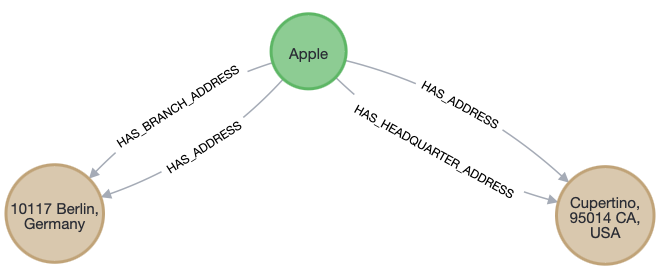

Into:

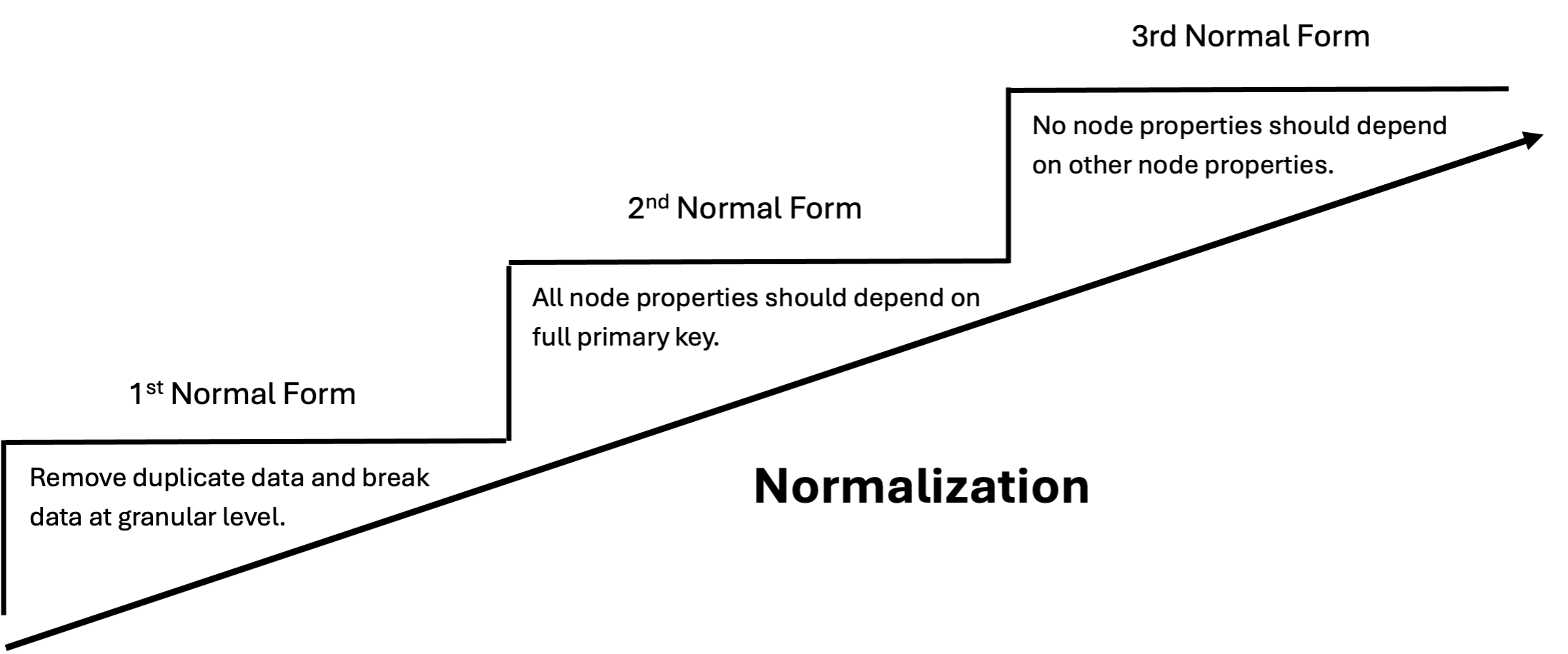

Relationships normalize data!

Adapted from Codd, E.F (1970). “A Relational Model of Data for Large Shared Data Banks”. Communications of the ACM. Classics. 13 (6): 377–87.

General relationships are qualified by their property and not their name. This makes it easier to query across all sub-types, and we use the property to discover these sub-types.

On the other hand, specific relationships are qualified by their name, which is more specific. It is then easier to query a specific sub-type but hard to discover all sub-types.

Nothing stops you from creating a general and specific relationship to model information to get the best of both worlds. However, keep in mind it will require more work when updating and writing information to the database.

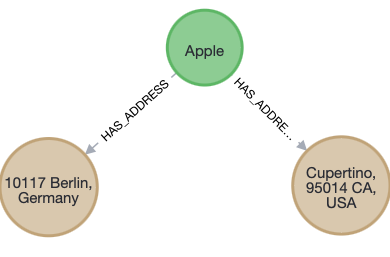

Dating a relationship is powerful and enables you to update and add information while keeping a trace of past information. For example, adding multiple HAS_ADDRESS relations to a company and specifying the dates that this relationship is valid. We can then easily see the history of this company’s address, including its current one.

Avoid modeling entities as relationships or relationship properties.

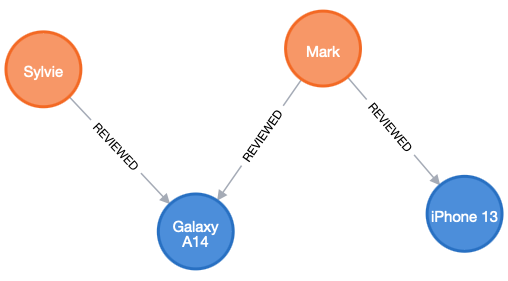

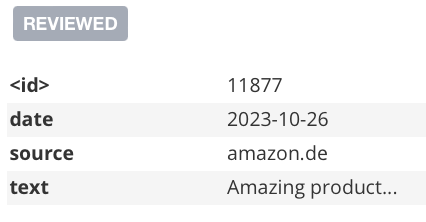

This makes it hard to associate more entities, hard to find relevant information and possibly duplicates data. A common tip is to see if an entity is “hidden” in the verb (action) of a relationship. Instead, model actions in terms of products, making it much easier to extend the model.

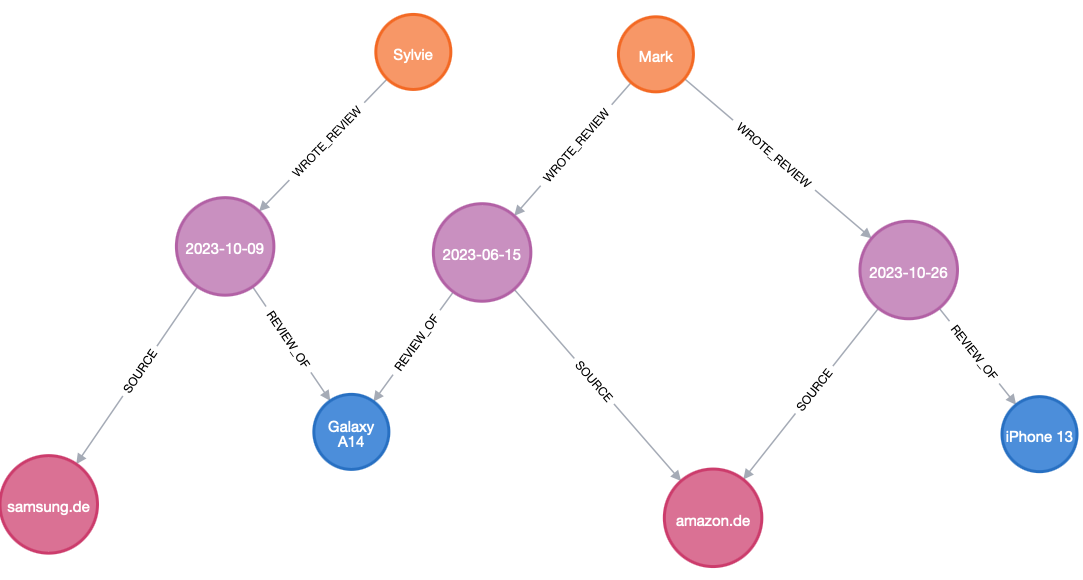

Here the Review is “hidden” in the REVIEWED verb/relationship, we should separate it out as a node.

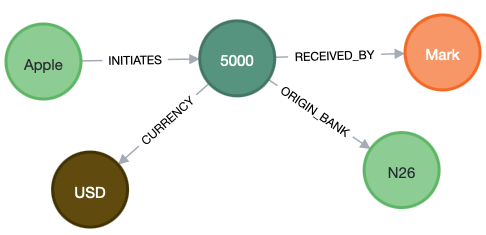

Usually, relationships should have few properties. If they don’t, or you see that you are filtering for the property of a relationship very often and during large traversals, you should consider reifying: factoring out a relationship into a node.

Reifying takes something abstract and makes it concrete. Reifying a relationship means turning that relationship (which might be representing an object itself) into a node, all on its own.

Into:

Here, a more complex reification:

Into:

In the second part we will have a look at labels, properties, constraints and indexes as well as how to make non-breaking changes to your Graph DB.

This is Part 1 of a two-part series on modelling a Graph Database in Neo4j, here is Part 2.

If you are interested in learning more about Graph Databases and Knowledge Graphs don’t hesitate to reach out on my LinkedIn or through YUKKA Lab.