A Leadership Seminar courtesy of the Swiss Army 🪖

Published:

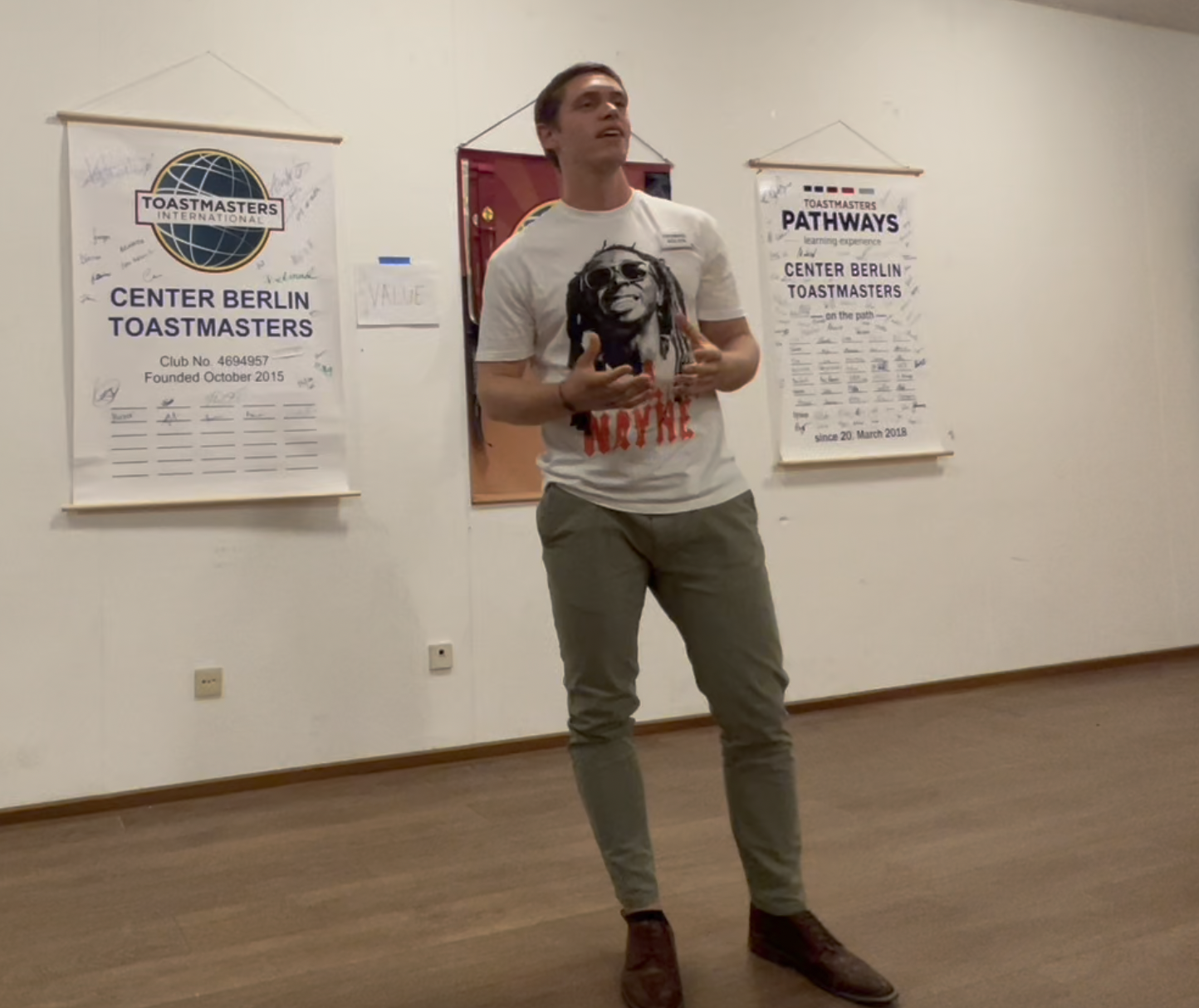

2-3 Introduction to Toastmasters Mentoring

This project introduces the value of mentorship and the Toastmasters view of mentors and protégés.

Purpose: The purpose of this project is to clearly define how Toastmasters envisions mentoring.

Overview: Write and present a 5- to 7-minute speech about a time when you were a protégé. Share the impact and importance of having a mentor. This speech is not a report on the content of this project. Note: Every member in Toastmasters Pathways must complete this project.

Speech timings: 5:00, 6:00, 7:00

Script

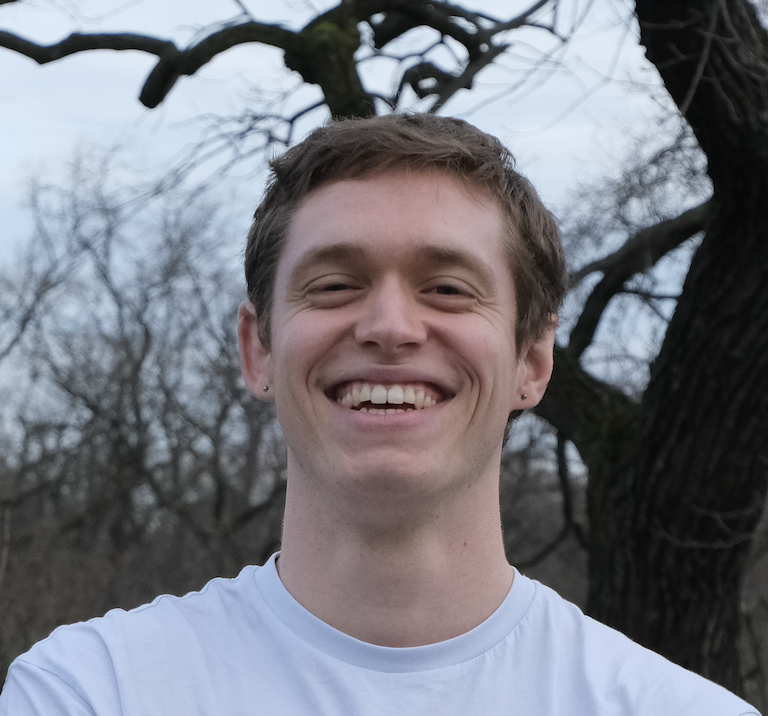

In a not so far away past, I wasn’t called Thomas. I didn’t smile, I didn’t laugh and, god forbid, I didn’t make jokes. Angry, bearded men would scream, insult me, and make fun of my French accent. I was told what to do, how to do it and with who, for every single second of the day. Now you’re wondering, where the hell did Thomas go, and how did he come back alive? Yea, I’m also wondering this myself.

Picture, young (younger) Thomas, he just finished high school abroad and didn’t know much about life (still doesn’t). After school, Thomas’ friends went backpacking in South America, partied in Coachella or started applying to Investment Banking internships. But Thomas had a better idea. He decided that he would go back to his native Switzerland: a country he’d never lived in and where he could only communicate with a fifth of the population, to voluntarily do his military service, responsibly using up taxpayers’ money!

Thomas needed a challenge, so he wasn’t going to sit around in the radio team or in logistics. He wanted to join the Special Forces of the Swiss Army, called the Grenadiers. I see all your surprised faces now: that guy who makes stupid jokes, smiles all the time and works in a tech startup, that guy was going to share a room with Chris Kyle, the sniper, and David Goggins, the mad ultra-marathon runner, no fucking way!

Well, young Thomas proved you wrong! He got in, despite his non-existent Swiss-German and his lack of right-wing sympathy! Grandma would always say: “The military service is a school of life” and however annoying that phrase kept getting, she was right. One thing that struck Thomas during his time there was the importance of leadership: as an 18yr old, Thomas needed people to follow, to look up to and to guide him. And he found just that.

Less-young, but still quite young, Thomas will now try to share some of his lessons he learned while being stuck in the middle of the Swiss Alps. I promise, this will be better than any of these leadership handbooks that tech bros and management gurus write about, and it’s courtesy of the Swiss taxpayer!.

First, as recruits in the Special Forces, you are part of a selection process for months. Everything you do and say is observed. They really try to push you to your limits, they don’t want to kick you out, they want you to quit. Days without sleep, countless hours of running in the middle of the mountains and ferocious hazing. This created a real atmosphere of terror. But what did keep me believing is how our superiors handled situations. They had all gone through the same thing as us, and oftentimes, as they did in the past, had it much harder. These people that led us were ice-cool under pressure, unemotional, precise and still relatively smart. I wanted to be just like them, they seemed so cool, who wouldn’t? As a leader if you want your team to follow you and do hard things, first, you need to show them that you can do it too, you need to lead by example.

Second, although the atmosphere with our superiors was terrifying, the atmosphere with our comrades couldn’t be better. As time went by, you realise that our superiors, indirectly, fostered that spirit within us. Doing hard shit with people is the best way to connect and bond, and we did. Collective punishment, the stripping of our individual identity and the breaking down of our ego might seem extreme in civilian life. But in the military it was an incredibly effective way to create a strong group dynamic. We had our own songs, initiations and traditions, not all of them safe or smart, but we didn’t care. We felt part of something bigger. Most of my comrades got tattoos of our unit, they still put it in their instagram bio and meet up every year for dinners. Lesson here is to foster a strong group dynamic, and you’ll be able to do things you didn’t think you were capable of.

Third, good leaders manage to make absurd tasks seem like the most noble thing in the world. We did some of the weirdest and pointless things. For the first 4 weeks, we spent 3 hours every single evening, brushing our shoes, until they shined. Since they were army boots that spent the whole day in the mud, they never did end up shining, and we had adequate punishment for that. Or, we had to make sinks and showers dry for inspections, which meant they were unusable for days. Or, when we forgot to zip up our pockets, we had to add a rock in that pocket, to remind ourselves of our mistake. This all sounds pretty stupid and frankly like a bad dream. But our leaders managed to make us believe that this was the right thing to do, in order to succeed. Lesson here is, if you want people to follow you, you need to instil a belief, a purpose in your team.

Yes, these implementations might not suit the alternative and progressive city that is Berlin, but I seriously think the principles do. I’ll be going back there in a week and a half, as we have yearly refresher courses, to get back into this scary world of mud, Swiss-Germans and organised chaos. And I’ll be reliving those important leadership lessons I learned: lead by example, create a team dynamic and give people belief. Now I think that these lessons are well worth our taxpayers’ money.